I imagine a lot of people checking this article won’t really know what’s meant by hard currency stores. What, like a place where you can’t use your bank card? No, no, it’s more fundamental than that! You see, in socialist countries, it’s pretty common for currency to be centrally managed. That’s why the state can simply decide to raise and lower the price of goods at their whim, the value of products and the value of money are decided by the state. At least in particular forms of centralised socialist countries (we could get into Yugoslavia and the likes, but let’s just not.)

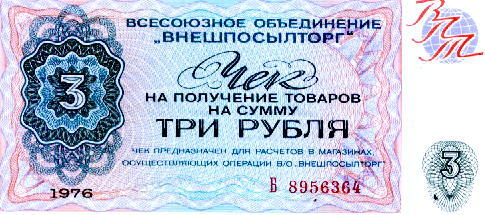

But, you might notice a problem here. Sure, this centralised currency works well for giving to citizens to pay for products owned by the state, only to be redistributed again as wages to another worker in the state, but what good is this to foreign countries? Not a lot. When the value of the currency isn’t tied to anything and can only be spent in the country it’s made, how the hell are you going to pay for imports from other countries? They don’t need your damn monopoly money! So that’s a conundrum. How exactly do socialist countries get money they can spend on imports, but also not give up control of their internal market?

Torgsin: Soviet Union

It’s July, 1931 and the Soviet Union is in the midst of its first five year plan. It’s not going too well. Production is lagging behind expectation and the struggle for collectivisation is ushering in a wave of food shortages that will reach all out famine by the following year. An absolute necessity to deal with these problems is hard currency that can be spent on the international market for modern machinery to complete the industrial plan and even improve harvest yields. But with foreign sanctions limiting what the Soviets can actually export for hard currency, how will you actually get it?

On the 5th of July, Vyacheslav Molotov decrees the opening of the Torgsin, a new chain of hard currency stores that sold many things not available in regular state stores. Even in a town ravaged by hunger, there was always the possibility that the Torgsin had grain to buy. You just needed to cough up some hard currency for it! Or failing that, gold and jewellery, things that can then actually be traded or sold for hard currency! Many Soviet citizens had such valuables and currency from before the revolution, holding onto it either for sentimental value or in the belief that things would return to capitalism one day and they’d need it.

The allure of the Torgsin stores, which rapidly spread throughout the nation proved enough to separate many from their hard-hidden cash, giving many at least a temporary reprieve from the growing scarcity in the early-mid 30s. After amassing somewhere in the region of 270 million gold rubles by January of 1936, the Torgsin stores were closed down. Perhaps citizens were running low on things to trade in, or perhaps the post-famine recovery had diminished the need for such hard currency stores. Whatever the case, the state monopoly on currency returned once more in the Soviet Union.

Hard Currency Stores Spread

While these hard currency stores lasted only a few years in the USSR and were seemingly deemed ideologically problematic and opposed thereafter, the legacy of their unquestioned success continued to loom large. As more socialist countries came into existence following the destruction of fascism, the first tentative steps towards emulation were being made. Perhaps the earliest were in freshly-socialist Czechoslovakia in 1948. Having the same problem as the Soviets with a lack of hard currency to spend internationally, a series of ‘Darex’ stores were available from 1948 to 1953 to both locals and foreigners to exchange their foreign currency for vouchers useful only at Darex stores.

After Czechoslovakia again ran into a lack of hard currency by 1957, the decision was made to resume the hard currency stores, now named Tuzex. Tuzex stores often sold high-quality locally made items for less than they cost in other state-run stores, the only caveat being that it required special vouchers that could only be bought with hard currency. While you needed hard currency to buy vouchers from Tuzex, high demand led to the growth of a black market for the vouchers, spreading this oasis of capitalism more widely through the nation.

Meanwhile in 1951, several large Chinese cities established a range of specialty stores for rare, valuable consumer goods that couldn’t possibly be acquired elsewhere. The Chinese revolution was a mere two years old at this stage and much of the nation had yet to be taken under full state control. These stores were the product of necessity, primarily serving important party figures and foreign expats or diplomatic staff. Unlike the Soviet Torgsin stores, these places wouldn’t serve average citizens even if they had the foreign currency to spend, they were little islands of capitalism and international trade for the foreigners living there.

In February of 1958, the first proper Shanghai Friendship Store was established. The meaning of the name ‘Friendship Store’ hints at its sole focus towards serving foreigners. While they had existed before, the scale had been escalated and the purpose formalised, no longer just the product of necessity for providing goods to those who needed them, the friendship stores became an avenue of attaining hard currency, something that rapidly grew in importance after the Sino-Soviet split of 1960.

The Khrushchev Era

While hard currency stores were first developed under Stalin, they’re pretty conspicuous in their absence after those few years in the 30s. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that Tuzex stores were brought to Czechoslovakia the year after Khrushchev’s denunciation of Stalin, marking the start of a thaw in relations with capitalist countries and a gradual economic reform that made concepts like hard currency stores more acceptable to the ruling communist parties. After Czechoslovakia and China, more countries began to follow suit.

The Polish company Baltona began sales for hard currency in 1956, the very same year as Khrushchev’s denunciations and beginning of reform. Bulgaria established the Corecom in 1960. The Soviet Union itself re-established hard currency stores in the form of ‘Beryozka’ in 1961. These were much stricter than the Torgsin of old, often being outright unavailable to regular citizens or at least catching the attention of local undercover agents if you bought from them when you shouldn’t be able to. Foreign currency was, after all, not supposed to be easily acquired. Unless you were an expat, a businessman who worked abroad or someone in the party, presence at these stores could be suspicious.

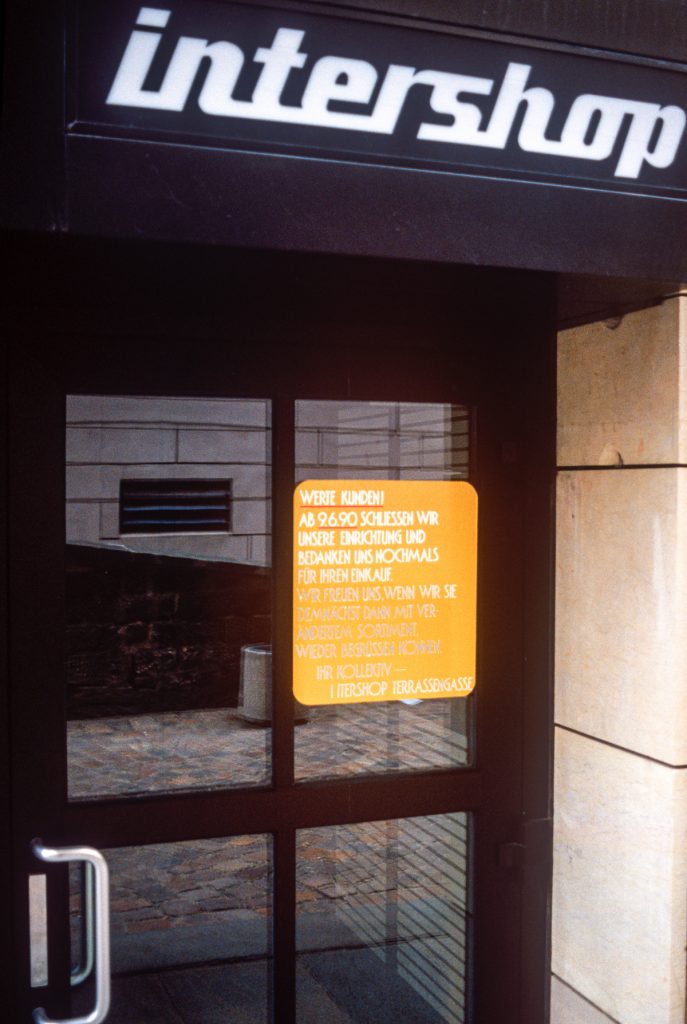

As the 60s wore on, still more countries created their own analogues of these hard currency stores. East Germany had Intershop, Romania had Comturist, Hungary had Interturist (notice the amount of ‘tourist’ in the names. Pretty obvious who these shops were aimed at). Though there were some countries that didn’t seem to have them at all. Albania most notably, adamantly refusing the Khrushchev style thaw advocated in other socialist countries, held to the Stalin line and seemingly never had such hard currency stores. Neither did other, poorer socialist countries, ones with little foreign tourism and who relied on socialist neighbours for their supplies rather than hard currency. Vietnam, Cambodia and of course North Korea, to name a few.

The Later Years

As the years passed by, the spread of these hard currency stores continued. The ideological shift under Khrushchev was maintained throughout allied nations and only deepened, even after the man himself was ousted. Tuzex stores in Czechoslovakia numbered a mere 14 in 1961, but by 1988, this had risen to 170. With Maoism repudiated in China by the end of the 70s, the Friendship Stores too began to spread rapidly and give an early kick-start to China’s economic opening to the west. The only socialist countries not to have them were either outside Soviet influence (like Albania) or simply unable to benefit from it (like Cuba).

With reforms deepening in the USSR and elsewhere, the seemingly sharp barrier between these islands of capitalist trade and the rest of the centrally planned economy began to blur. In Czechoslovakia, the practice of buying Tuzex vouchers on the black market was so common that a movie about it was released in 1988, Bony a klid. While some countries put in great efforts to curtail these black market practices, the gradual liberalization only made it more inevitable and pervasive.

In 1988, under Soviet leader Gorbachev, the rules in Beryozka stores were changed as part of Soviet ‘perestroika’ (restructuring of the economy). When before you needed to have foreign currency exchanged into vouchers that could be spent there, this voucher system was abolished and trade in these hard currency stores suddenly became accessible to the average Soviet citizen. Although… With the rapid sweep of privatizations to go along with it, these stores had lost their purpose. They had become little more than a hub for black market trading in the rapidly collapsing Soviet economy, so by the start of the 90s, most Beryozka stores were shut down for being simply unprofitable.

Tuzex limped on until 1992 before being shut down. Intershop was dissolved in 1990 while Baltona found itself privatized and continues in some form to this very day. Comturist in Romania largely shut down, only for its assets to be bought by a new company, also named Comturist in 1990. With the collapse of socialism itself, the system of planned economy dissolved. There was no more need for hard currency stores in capitalism and so, the story of these fascinating socialist stores came to an end.

Hard Currency Stores after the USSR

With the collapse or reform of nearly every socialist country between 1989 and 1991, hard currency stores were seemingly a relic of a bygone age. Certainly not relevant to the new neoliberal economic landscape, where the free flow of currency pegged to the US dollar was the measure of any economy worth its salt. But you see, not all socialist countries were down and out. Some that had never before needed such a store were forced to make adjustments if they wanted the hard currency necessary to stay afloat.

Most notable in this case is Cuba. The collapse of the USSR led to a massive economic downturn in Cuba, which had been reliant on subsidized trade from its socialist partner to offset the hardships imposed by America’s embargo. There had never been much need for hard currency, but now Cuba was on its own. Alongside a push to start bringing in foreign tourists, Cuba decriminalized the use of the US dollar in 1993. This was accompanied by the opening of new ‘dollar stores’, where items could be bought only with such hard currency. Not only did this appeal to foreigners, but it was to encourage relatives in America to send dollars to their families in Cuba.

In 2003, the dollar was once again banned, but replaced with the Cuban Convertible Peso. If you want to know about those, we have a whole article on them here! With Cuba’s ‘special period’ over, it was felt that it was now safe to tighten the reins a little bit more, though these hard currency stores remain, often still referred to colloquially as dollar stores.

Besides Cuba, there’s another socialist holdout that definitely carries on the legacy of these special hard currency stores. Good ‘ol north Korea. The DPRK, as you might have noticed from us by now, does take in quite a lot of foreign tourists and naturally, they want people to spend hard currency there! The hotel will naturally have its own stores with special prices for those with foreign currency, while even shops visited by DPRK citizens may have special pricings for those on tours. Uniquely available which most other socialist countries would never allow is the Kwangbok Department Store and Supermarket which allows you to exchange for local Korean won and spend just like the locals!

Conclusion

As it stands, Cuba and north Korea are the two countries left where such things as hard currency stores are actually needed. Remnants exist elsewhere. It’s not too hard to find the old buildings simply functioning as normal shops now, while the likes of China’s Friendship Stores continue to exist and even see renovations as a new lease on life. Historical curios to be sure, but it doesn’t compare with the real thing. A fascinating clash of socialist planned economics and a necessity to trade with the capitalist world on its own terms, hard currency stores are a unique feature of socialist countries.