So my old article got outdated pretty damn quick. I anticipated the Taliban getting into government in some form, but it looks like everything just got steamrolled. Ah well. While I’ve clearly demonstrated I’m terrible at seeing into the future, we can at least look to the past to maybe get a few hints of where things may be going now. What better place to start than with the movement that fought the Taliban the first time around, the Northern Alliance.

Before the Northern Alliance

To get the Northern Alliance and the state of Afghanistan in general, it’s important to contextualise them. After all, it’s not as if resistance to the Taliban rose out of the ether. It has its roots in the government that came before, from 1992 to 1996, typically known as the Islamic State of Afghanistan. Which was… Not a very stable government to say the least.

You may know that the the Soviets and their puppet government were fought by the ‘mujahideen’. That’s a pretty broad term because it encompassed a lot of different groups, often representing different demographics that didn’t entirely trust each-other. One can imagine that this presents really shaky grounds for establishing a government, but actually, most were on the same page. Before even setting foot in Kabul, seven of the largest Sunni mujahideen groups united into what was known as the ‘Islamic Unity of Afghanistan Mujahideen’, otherwise known as the Peshawar Seven, in reference to where their government in exile was located.

The Peshawar Seven were overwhelmingly made up of Sunni Pashtuns, as well as a large party representing Sunni Tajiks. They had their differences, but differences they felt they could get over politically. Representing the smaller population of Shia Muslims in Afghanistan were the so-called Tehran Eight, who while not part of the Peshawar Seven’s government, were not on hostile terms with them and later organized a degree of recognition for the newly formed government. That’s a whole lot of groups entering Kabul with little reason to hate each-other. With one caveat.

For all the groups that were on the same page, one was not. It was an important one. The ‘Hizb-e Islami’ party, or the Islamic Party, had two factions with both in the Peshawar Seven. One of those factions was led by a man called Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, who was the man to fuck everything up for everyone. While the other parties were tense, but still willing to take a crack at a unified government, Hekmatyar felt that his military might was great and submitting as a mere partner among many would lead to a weak Afghan state. Announcing intentions to march on Kabul and seize it for himself, before any kind of government was ever installed, the war began anew.

Civil War: 1992-1996

So everything went to shit. Almost immediately, the forces under Hekmatyar began firing thousands of rockets indiscriminately into Kabul and almost completely fracturing the peace agreements. Even worse, another faction of the Peshawar Seven, closely aligned and financed by Saudi Arabia, began violently slaughtering Shia civilians and factions of the Tehran Eight. What remained of the alliance struggled to mediate peace between them with temporary success, but it was clear that faith in the new government was rapidly collapsing.

Even when Hekmatyar was promised the position of prime minister, he attempted to shoot down the plane of the new Afghan president within a week. It’s largely agreed now that his forces were being funded, armed, trained and in many ways controlled by the secret services of Pakistan, all long before the Taliban came onto the scene. They demonstrated a clear lack of interest in civilian casualties, with most of the thousands of fired rockets landing in civilian areas, along with many notable massacres and the deliberate destruction of electricity infrastructure, water facilities and the blockading of many food convoys.

Outside of Kabul, things were even worse. Most of the military forces intended to form the new government were fighting a brutal battle in the north around Kabul, while other cities were often host to unaligned tribal groups who simply operated as warlords and bandits. Kandahar in particular became known for lawlessness and constant infighting, setting the stage much later for the rise of the Taliban. As time wore on, the idea of a unified government for the country must have seemed like a sick joke.

As the carnage raged on in the north of the country, the lawless south provided an opportunity. In the midst of the chaos, a new movement arose with the backing of Pakistan, who had evidently recognized that Hekmatyar’s forces could never claim to be a uniting, liberating force for the country. From the outset, the Taliban promised to be just that. In the power vacuum of Kandahar, they scored their first major victory by ending the chaos and banditry. Who cared if they were religiously strict, they weren’t going to just rape, rob and kill you on a whim.

The Taliban surged rapidly through the south, gathering momentum as they went while the moribund factions in the north simply continued their brutal stalemate at the cost of many Afghan lives. In this environment, it’s not surprising that the Taliban met success in nearly every campaign they started, even routing the forces of Hekmatyar and seizing his weapons. Speaking of that cheeky bastard, he went on to become prime minister in a power-sharing government in May 1996. If anything, this just killed whatever legitimacy the government had in even Kabul, as the victimized populace were subjected to his own harsh religious rule. Kabul fell not long after.

Founding of the Northern Alliance

At long last we get to the Northern Alliance. Given the state of the ‘alliance’ of mujahideen forces in the north of Afghanistan, it seems like a pretty laughable concept now. But the Taliban at last provided a reason for various factions to align themselves. With Kabul gone, what were they to do? Where were they to turn? There were two figures, soon to be pivotal in the Northern Alliance, that the average non-Taliban supporting Afghan felt they could trust. Ahmad Shah Massoud and Abdul Rashid Dostum.

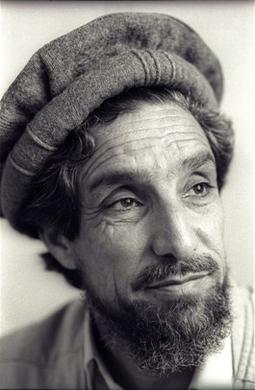

So who are they? Massoud frankly deserves an article all to himself. An early guerrilla fighter with the mujahideen, Massoud was an ethnic Tajik from the Panjshir valley in northern Afghanistan. While a devout Sunni Muslim himself, he was described as one of the only Afghan leaders who truly wanted a pluralistic society and was willing to work with other factions. He was the defence minister of the Islamic State of Iraq during those brief few years of civil war and led the largest military faction at that time, gaining major victories with his military influence from Che Guevara and Mao Zedong. He was also known as the Lion of Panjshir, so… Pretty cool.

Dostum is quite a different matter. From an ethnic Uzbek background, Dostum was far away from many of the other factions of the Peshawar Seven. He had been a prominent commander under the communist government until his defection in 1992, leading one of the most highly trained, equipped and secular factions to come out of the collapse of the government. His movement trended towards minorities, particularly Uzbeks, as well as secularists and even some socialists. While carnage raged in Kabul, he actually held his own pseudo-state on the Uzbek border which was comparatively economically flourishing and even had its own money.

Massoud and Dostum did not always see eye to eye. There was a period of a few months where Dostum actually decided to ally with Hekmatyar instead, but he eventually switched back. On his own, Dostum didn’t command the support of more traditionalist Muslims or other minorities, while Massoud didn’t as much appeal to secularists and former soldiers of the regime. Relying on the Taliban’s surge upwards from the predominantly Pashtun south, Dostum’s territory along the border with Uzbekistan and Massoud’s along the north-east, a core defensive base was established. Soon, other anti-Taliban forces flocked to fight under the banner of the Northern Alliance.

The Early Northern Alliance: 1996-1998

With the Northern Alliance established, the anti-Taliban resistance was ready to sweep the country! …Except that’s not really what happened. As soon as 1997, a crushing blow was delivered to the movement. You see Dostum had an ally, Abdul Malik Pahlawan. He was not a good ally. In 1996, after accusing Dostum of murdering his brother, he secretly worked with the Taliban to coup the stronghold city of Mazar-i-Sharif and hand it over to the Taliban. This fractured within months as the ethnic Uzbeks of the region realised they were essentially being conquered and having their way of life eliminated, so the Taliban were driven out again a few months later, the Northern Alliance’s control re-established.

Sounds like a bit of a footnote, right? Not really, because it set the scene for brutality going forward. Pahlawan wasn’t content to have won back the province. Taking around 3,000 Taliban fighters prisoner, they were all summarily executed and buried in mass graves by Northern Alliance forces, with Pahlawan personally carrying out many executions. While this drove off and demoralized the Taliban in the short-term, it also caused revulsion among many Pashtun Muslims in the Northern Alliance who saw Pahlawan (rightly) as a traitor both to the Northern Alliance and the Taliban. Defections began and the stage was set for a Taliban counter-offensive.

This fracturing led to Dostum returning and attacking Pahlawan’s allies and the Taliban simultaneously, driving Pahlawan into exile and keeping the Taliban offensive at bay for a little while. It was a crushing blow to the Northern Alliance’s legitimacy because they just couldn’t stop murdering each-other. Massoud desperately attempted to negotiate, as he had many times before, but to little success. While the Northern Alliance rapidly ran out of allies, the Taliban were only gaining more and more. So much so that a new offensive in July 1998, roughly a year after the Taliban were kicked out of Mazar-i-Sharif, managed to seize the city on the 8th of August.

Given the result of taking the city last time was 3000 Taliban troops dead in the ground, the first thing to happen were horrific reprisals. The predominantly Shia population who had been represented by Pahlawan, the Hazara, were sought out and massacred, along with many Tajik and Uzbek civilians. On the very same day, Pakistan recognized the Taliban as the legitimate government of Afghanistan, having seized the last major city in Afghanistan. Hardly surprising seeing as many Pakistani soldiers (allegedly) took part in the seizing of the city, as well as providing air-support. Soon after, Saudi Arabia and the UAE followed in recognizing the Taliban, leaving the Northern Alliance in the cold.

Massoud Leads the Northern Alliance Alone

With Mazar-i-Sharif seized by the Taliban, Dostum was forced into exile in Turkey. This left Massoud as essentially the sole face of the Northern Alliance, all the way from his home in the Panjshir Valley. He had successfully defended it from communists in the 80s and now it remained one of the few strongholds safe from Taliban attacks, a position now hanging extremely precariously as the outside world increasingly accepted the Taliban’s rule and the creeping, heavily armed and funded forces of the Taliban crept ever closer.

Many of those who fell to the Taliban were simply bought. Mazar-i-Sharif partly fell because of bribes to commanders to switch sides, so it’s unsurprising that Massoud was offered high posts in the new Taliban government. He refused, citing his irreconcilable belief in democracy. Would bring a tear to the eye of a CIA agent that, a highly trained, well-loved and charismatic Afghan revolutionary who prized democracy above power? Why aren’t all the massive piles of cash and guns going to this guy and the Northern Alliance? Well, about that…

In 1997, a diplomat for the US state department offered Massoud advice. Surrender to the Taliban. He refused. You see, times had changed since the 80s, the government didn’t give a shit about the Taliban brutalizing people, the issue had always been that the Soviets were there. As Biden himself has been stating now, the US was never in Afghanistan to help its people, it was always about defeating enemies. At this time, the Taliban were not an enemy. In fact, the Americans repeatedly tried to dissuade the Northern Alliance from launching anti-Taliban offensives and when one US Defence Intelligence Agency figure travelled to meet Massoud in 1998 and relayed that the Taliban were forming alliances with international terrorists, she was fired.

The flood of arms and aid that had poured onto the mujahideen in the 90s was long gone. The Americans and Europe wouldn’t give Massoud jack, all while Pakistan, the Saudis and others propped up the Taliban both economically and often militarily. Often, this was against the advice of their own allies, with CIA operatives in Northern Alliance territory almost unanimously calling for the US to aid them and believing the Taliban were a much greater threat than they were willing to accept. India, for its part, actually did provide some aid to the Northern Alliance, though this mostly makes sense in the context of the proxy war with Pakistan.

Assassination of Massoud and 9/11

Those are two pretty huge topics. And they happened to occur within days of each-other. You see, the US largely didn’t care about the wide presence of Al Qaeda fighters in Afghanistan. There was an attack in 1998 that caused some level of co-operation between the US and Massoud, but it was extremely limited and Al Qaeda were extremely underestimated. What’s more, Massoud was clearly underestimated because he was actively trying to warn of the attack for months.

In April, Massoud was invited to Brussels to address the European Parliament. He warned specifically of imminent large-scale attacks on the US mainland. You might notice that goes beyond prophetic, this guy clearly knew something the west didn’t. It’s hard to know how he got the information to begin with, but given his forces were in the heart of Al Qaeda’s territory, there’s no reason to believe he couldn’t have gotten access to that kind of info. But naturally, the arrogance of the US towards Massoud left this information not taken seriously.

On the 9th of September 2001, two Al Qaeda militants in disguise as press reporters were granted an interview with Massoud after weeks of build-up to gain his trust. During the interview, a bomb hidden in their camera was detonated, dealing Massoud grievous wounds that ultimately took his life en-route to the hospital. Hundreds of thousands in Northern Alliance territory attended his funeral, having lost the one figure holding them together since the Taliban’s seizure of power. Just two days later, the planes hit the towers on 9/11 and American policy towards the Taliban and the Northern Alliance shifted drastically. For all we know, had they only listened to him sooner, the attack may have never happened.

By this stage, the Northern Alliance’s territory was mostly confined to about 10% of north-eastern Afghanistan and was slowly but steadily losing even that ground. With the loss of their most capable and loved military leader, it seems likely that further losses would be inevitable and the last unseized territory would fall, no-doubt to follow with the massacre of many and the subjugation of all. After all, there were no sympathisers who just happened to be in Northern Alliance territory anymore. There was no-one for the Taliban to ‘liberate’ in their own sense. Only conquest. But… It didn’t quite go that way.

The US Invasion

So yeah, we know how this goes. Just two days after the assassination of Massoud, far too soon to act on the potential military gains, Al Qaeda fly planes into the World Trade Centre in New York. The Taliban likely had no idea, given they tried hard to express they posed no threat to the outside world. They were acutely aware of their losing military situation. But with Uncle Sam a’knockin, focus shifted from crushing the Northern Alliance to not being invaded. Something made difficult by the stubbornness of the Taliban’s leader Mullah Omar, as well as the clear desire for any excuse from America to claim its pound of flesh in retaliation.

The Americans demanded the Taliban turn over Osama bin Laden immediately and submit to unrestricted inspections of Afghanistan’s territory for training camps. Omar didn’t refuse them as such, rather he asked for the proof that it was Osama who ordered the attack, who at the time denied involvement. America took that honestly fairly reasonable demand for evidence as refusal and began a large-scale bombing campaign. Contradictory positions were taken by various Taliban leaders trying to save their regime while Omar stood solidly in his refusal.

Meanwhile, all the funds, arms, intel and aid the Northern Alliance could dream of was being thrown at them. New offensives were launched with the aid of American bombings and the Taliban were rapidly driven back. By November 11th, Mazar-i-Sharif was once again in Northern Alliance hands, under the control of Dostum. The following day, the Taliban fled Kabul in the night to disperse into the countryside and hide. Holding territory was clearly impossible against a foe as militarily powerful as America… Though as we certainly know now, the strategy of taking to the countryside works pretty damn well in the long-term.

On November 23rd, the last Taliban stronghold city in Kunduz surrendered to the Northern Alliance. What remained were isolated bases that didn’t last into mid-December. In just about three months, the Taliban went from controlling 90% of the country to being driven out of all but the most isolated villages and mountains. Mullah Omar, the Taliban’s leader, is believed to have escaped from Kandahar in early December in a motorcade, fleeing to the mountains and ultimately never being captured. The Taliban were defeated. It was now up to the Northern Alliance to rebuild.

Rebuilding Afghanistan

On the 6th of December, Hamid Karzai was informed he would become the new president of Afghanistan. Who the fuck is Hamid Karzai? Well you might have noticed that Massoud was the only significant face of the Northern Alliance for many years, so it’s easy for other figures to fall through the cracks, especially having a total of two days between losing your leader and being overshadowed by the US. Hard to really establish a prominent new ‘face’. But anyway, Karzai got his start as a fundraiser for the US-backed mujahideen. The roots of that particular foreign intervention bury deep in Afghan politics.

Not long before the Taliban seized control, Karzai fled to Pakistan due to the massive internal conflict in Kabul. His relationship with them at first was cautiously positive, to the point of wanting to represent them in the UN, a position his uncle had held in the 60s, though the Taliban didn’t quite find him trustworthy for the task. For a while, he was actually an Afghan royalist, pushing for the return of the king Mohammed Zahir Shah, a broadly popular figure who’d been exiled from the country many decades before. It was only after his dad was assassinated by the Taliban in 1999 that he fully backed the Northern Alliance.

Karzai was made the immediate leader of an undemocratic interim government. That’s not too abnormal, interim governments are only supposed to wait out the transition to an elected government. What was a bit unfortunate was how rigged the following election was. Between the 11th and 19th of June, a ‘loya jirga’ was held, this being a traditional ‘grand assembly’ that in this context, was used to elect the new Afghan leader. Those selected to form the assembly were nominally elected to their position, but many were outright selected and local warlords tended to pressure their own figures into the position.

Even worse, the former King Shah returned to Afghanistan and announced his willingness to return to being head of state if the election approved. Mysteriously, he and other notable political rival, Burhanuddin Rabbani, former leader of the Islamic State of Afghanistan interim government, both bowed out of the election under US pressure, leaving one woman candidate to stand against Karzai. This, along with the new government’s near complete lack of authority outside Kabul, set an early stage for disillusionment with the new government and a resurgence of the Taliban, the outcome of which we’ve just recently come to see.

Conclusion

With the war effectively ‘won’, the Northern Alliance faded out of relevancy and largely out of existence. It had no purpose once the war was over after all. Without a Taliban to unite against, many of the disparate groups fragmented, forming new political parties and sometimes new armed groups to try and influence Afghan politics however they saw fit. Many key figures continued to operate high places in the Afghan government, at least up until its recent collapse, with figures like Dostum fleeing across the border into Uzbekistan.

In 2004, Afghanistan held its first proper democratic election. Karzai once again won, with 55.4% of the vote, over 4.4 million… Granted, this was out of a population of around 25 million at the time, but the vast majority didn’t vote, with some later elections having an even worse turnout. Many candidates had boycotted the vote and even with all that working in Karzai’s favour, there were apparently mass reports of voter fraud. If you don’t believe it, Karzai’s response to claims of fraud in the 2009 election was to say “There was fraud in the 2004 election too.”

Sure enough, he won the 2009 election. This remnant of a sort-of Northern Alliance figure as the head of the Afghan government probably wasn’t doing it much favours with its public image. This time his proportion was even more pathetic, a mere 2.3 million out of a population of 28 million. Even if we argue that many weren’t of voting age or registered to vote, that’s a shockingly low public mandate that may help to explain the lack of faith in Afghan democracy.

As for the Northern Alliance now? Well… You might be surprised to hear that there’s a successor organization. With a lot of fascinating links to the original. If you’d like to know more about that, you’re just going to have to wait and see. Or use Google yourself, I’m not the boss of you.