At YPT, we’ve got a real interest in separatist movements and the idea of new countries. We’ve written a few articles on the subject! Being from Ulster myself, I think it’s worth discussing a rather unknown group, the Ulster nationalism movement. But! First of all. What even is Ulster anyway and what’s an Ulster nationalist?

What is Ulster?

Ulster (known as Ulaidh in Irish) is one of the four provinces of Ireland, consisting of nine counties in the north of the country, including the six counties occupied by Britain. It has a long history of traditional Gaelic culture and a population of just over two million people. Ulster is also the closest part of Ireland to Britain, making it the most thoroughly ‘Anglicised’ part of Ireland, with colonisation beginning in the 1600s and replacing the Irish landowners with English and Scottish ones. For this reason, Ulster is the only Irish province to have a large protestant population, at around 42.7% in 2011.

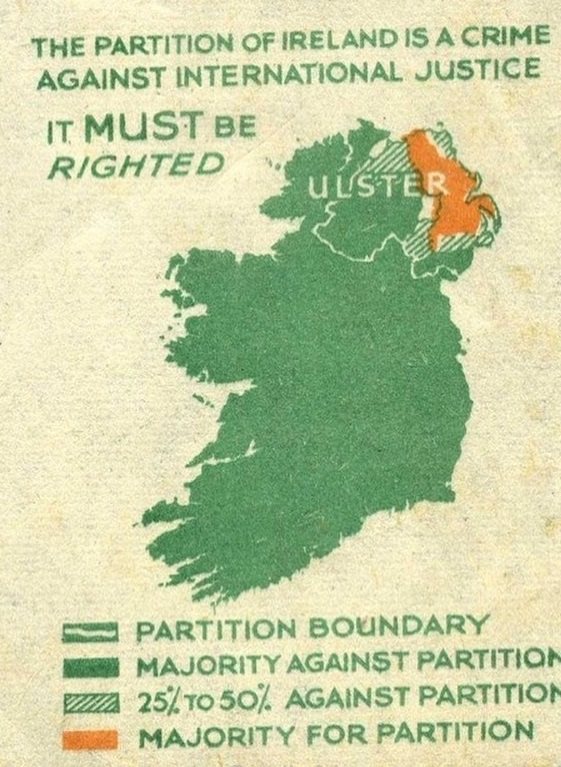

For a very long time, Ireland was entirely controlled by Britain, though sentiment for an independent Ireland was overwhelming across the country, with the exception of parts of Ulster that had been more heavily colonized by English and Scottish settlers. In the 1918 general election, Irish unionists (pro-Britain) got 29% of the vote nationwide, but only 6% in the 26 southern counties that would become the Irish free state, further emphasizing the sharp divide between the Irish and English/Scottish settler population.

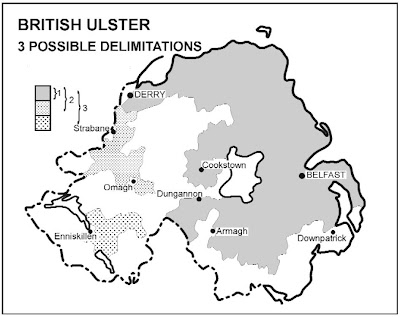

Although Irish independence was clearly overwhelmingly popular, Britain didn’t want to give up complete control. A compromise was reached where six counties in Ulster would be given the option to vote to remain in the union, which they subsequently did. But why six counties rather than the nine that make up Ulster? Simple. Unionists (identified by their protestant heritage in the census) only made up a majority in four of the nine counties, meaning that a nine-county vote would see them fail, while a four-county state would be too small to be viable. As a result, the Catholic (pro-Irish) counties of Fermanagh and Tyrone were included.

This gerrymandering allowed the vote to pass, while the new southern Irish government capitulated to the demand, an act (among others) that sparked a civil war between factions of the Irish Republican Army in support of this limited independence and those who wished to fight on. Meanwhile, the new northern state (known as ‘Northern Ireland’) began violently cracking down on Irish Catholics, with many burned out of their homes and evicted from their jobs by protestant supremacists in groups like the Ulster Volunteer Force, as well as by the state forces themselves who were made up of these same protestant supremacists. The first northern Ireland prime minister James Craig boasted of having a protestant state and protestant parliament.

Since then, the six counties have been a frequent point of conflict, with protestant supremacy challenged by civil rights demonstrations in 1969 that faced extreme violence from the state and unionist citizens, culminating in Bloody Sunday in 1972, in which 14 civilians were shot dead by the British army. The conflict spiralled, with surging paramilitary groups for both Irish independence and British unionism and regular riots that resulted in over 3000 deaths by the 1990s. The conflict officially ended in 1997 when an agreement was signed to let the IRA’s political wing participate in a devolved government, with expanded rights for Catholics. Despite this, many problems continue to simmer in the background, with violence occasionally flaring up.

What’s Ulster Nationalism?

So I think I’ve explained pretty well that there’s two main sides to the conflict in the north of Ireland. There’s those who believe that Ulster (or at least the six counties that the British control, but they just call it Ulster anyway) should be united with the Irish free state and those who believe that Ulster should remain part of Britain. And then there’s the third path of Ulster nationalism, who believe that Ulster should just be its own independent nation. How the hell does that work?

The origins of Ulster nationalism can trace back at least as far as just after WW2, where the collapse of the British empire led to existential fears for unionists who didn’t want a united Ireland. What they called for was ‘dominion’ status, in which the northern state would become independent but remain a part of the empire, similar to the status of Canada and Australia today. While there was talk of such a scenario, it wasn’t revived until the 1970s when escalating civil war in the northern state made many fear that a united Ireland was on the horizon. Indeed, Britain had outright considered either re-partitioning Ireland to give more land to the free state, or simply deporting Catholic families.

Some of the justification centres around the Ulster-Scots people, those most directly descended from lowland Scottish colonists in the 1600s. They had their own unique dialect and cultural norms that some have argued makes them a separate national identity. Indeed, the 2011 census noted that about 8.1% of the north’s population has at least some knowledge of Ulster-Scots language, though only 0.9% can speak, read and write it. On this same census, it’s notable that 21% of the population would consider themselves ‘northern Irish only’, with a further 8.3% considering themselves a mix of northern Irish and one or more other nationalities.

Typically speaking, Ulster nationalism is a unique phenomenon to northern Irish protestants, being rooted in a desire to retain some form of union with Britain while also questioning the future of its current direct political unity. That said, there are some who believe in full independence, either leaning on this idea of a unique Ulster-Scots identity or some who believe that the sectarianism in the country between Catholics and protestants can only be overcome through independence. It’s rare, though not completely unheard of, for Catholics to take such a position.

Ulster Nationalism Grows

In 1972, nearly 500 people were killed as the growing conflict spiralled further out of control. The question of Ulster nationalism gained a newfound relevancy, leading the Ulster Vanguard party to issue a pamphlet that year outlining their case for Ulster nationalism. In it, they call for an independent union of Britain, southern Ireland and the six counties, where all sides would mutually agree upon their relationships going forward. It suggests that this would satisfy both communities, with Irish republicans being able to agree to stronger ties with Ireland alongside the people of Ulster maintaining British citizenship, or sharing matters of foreign policy and so on.

Notably, it casts a great deal of blame for the deteriorating situation on Britain itself, claiming that Britain does not consider the people of Ulster to be British and share the same goal as the south of Ireland, as well as criticising the British direct rule of the northern Irish government at this time as unacceptable and colonialist. While the party was most certainly patriotic towards Britain, there was still an inherent otherness that separated them, a conflict that furthered the desire for a more independent government akin to the dominion status proposed long before.

The idea of Ulster nationalism gained some traction, soon growing within the unionist paramilitary, the Ulster Defence Association (UDA). The UDA, which killed several hundred innocent people throughout the conflict, mostly through assassinations, spree shootings and bombings, began to flirt with the idea in 1976 through its political advisory wing, eventually releasing a document in 1979 called Beyond the Religious Divide. The document rejects the idea of a shared union with both the south and Britain, instead arguing the relations must be broken with both, as it suggests the northern Irish people are considered second class citizens in both Britain and southern Ireland.

They suggested a constitution and a bill of rights be formed, along with a supreme court and to have a phased withdrawal, with a prime minister elected after 8 years and for full independence to be attained within 16-20 years. The proposal openly emulates the US political system, seeing it as the most fair way to cater to both protestant and Catholic citizens. After the UDA’s electoral hopes were dashed in 1982 after an abysmal election result, the movement largely dropped the idea of Ulster nationalism… At least for a while. Meanwhile the idea limped on through a few other small groups, such as Ulster Third Way who are also known for being neo-Confederates for… Some reason.

As the conflict progressed into the early 90s, winding down towards a peace settlement, the UDA released a new document in 1994 with an even more controversial plan. They called for the repartition of Ireland once again, demanding an ‘ethnically protestant homeland’, in which overwhelmingly Catholic areas would be handed over to the south. Sounds somewhat reasonable, it is an old idea after all. Though the kicker is what they wanted to do with the Catholics left in protestant areas… As they claimed, they should be ‘expelled, nullified or interned’. So yeah. Essentially genocide and purging of all Catholics from a new ethnostate. The idea gained some support even from mainstream unionists, but ultimately went nowhere.

Conclusion

Since then the idea of Ulster nationalism has remained dormant. The wrapping up of the conflict may have eased fears of an imminent united Ireland, though recent demographic shifts and the collapse of mainstream unionist political power may stoke up fears enough for a return to the idea some day. Ulster nationalism has always been a last-ditch effort to save unionist domination when all seems lost. It’s not a particularly coherent philosophy most of the time and its support has always been fringe but fleeting. Nonetheless, it makes for one of the more niche and fascinating separatist movements in the world.