Before we get to the Zapatistas, let’s talk about Mexico. Sunny and beautiful Mexico. There’s certain images that may come to mind when you think of it. Maybe you’re seeing the endless expanses of rugged desert dotted with cacti and animal skulls or maybe you’re thinking of a bright and cheerful mariachi band. You may be seeing everything drenched in an unpleasant yellow filter, like you constantly get in Hollywood movies. Or maybe you’re thinking more negative still and picturing the violence of the cartels.

Well I think most people are aware that these images, even the positive ones, are largely stereotypes. Mexico is absolutely huge and extremely varied. Take a photo in most parts of Mexico and you may not even know what country it is at a glance! This is especially true when you get deeper into Mexico and see the surprising things on offer. For example, let’s look at Chiapas. Given we see images of Mexico mostly from the American perspective, Chiapas gets left out for many reasons, a big one being that it’s the southernmost Mexican state, bordering Guatemala and as far from America as you can get. So let’s check out a photo taken in Chiapas, shall we?

…Huh.

Zapatistas in Chiapas

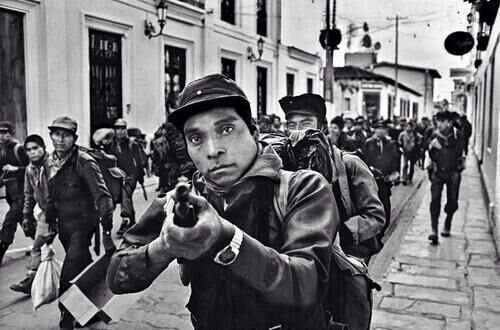

So yeah, there’s something going down in Mexico alright. That being the Zapatista Army of National Liberation, often simply called the Zapatistas. You may be getting worried already and wondering if the country is about to blow up in a civil war. I mean, look at them! Wearing balaclavas and red scarves, carrying weapons and looking just like other regional guerrilla groups like FARC. But you should know that the Zapatistas have been there since the 90s and despite all their military garb, they have a fairly live and let live relationship with the Mexican government. I’ll explain how that all happened later in this article.

So to give a brief overview, about a third of Chiapas, particularly in the west of the state are effectively led by the Zapatista movement who have their own democratic structures, schools, farms, hospitals and more. Almost 400,000 people are estimated to live in this territory and the Mexican military generally stays away from it. What’s more, the territory has gradually been expanding over the years rather than retracting, albeit not through military action. They have no real leader (though I’ll elaborate on this later) and nobody is more authoritative than anyone else. They espouse their own belief system, Zapatismo, which is a fusion of anarchism, Marxism and more traditional indigenous Chiapas values.

The Zapatistas survive through the genuine support of the people there, coupled with a fragile relationship with the Mexican government that lets them pick and choose which battles to fight out. Technically, the territory they control is still Mexico’s and if they really wanted, they could storm it and seize it all back, but due to the local hostility and the economic insignificance of the reason, there’s not been a major push to do so. As long as the Zapatistas don’t overstep their mark, they’re free to function as they please.

How the Zapatistas Began

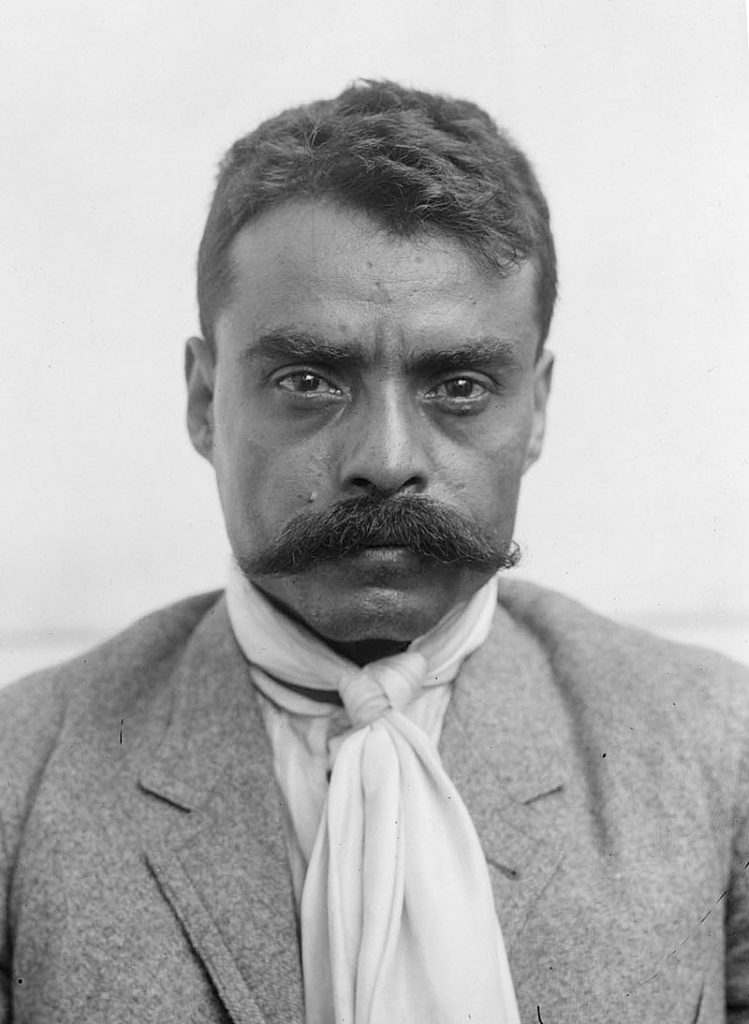

Before there were Zapatistas, there was Emiliano Zapata, where the movement got its name from. Zapata was a major figure in the Mexican revolution of 1910-1920, during which he led a large army of mostly indigenous peasants on a campaign to reclaim stolen land and redistribute it to those who worked on it. When the revolution was initially won, the new Mexican president refused to accede to Zapata’s pro-peasantry demands and the war continued, right up until Zapata was assassinated in an ambush in 1919.

While Zapata was not successful in his revolution, the subsequent years saw many of his allies rise to major political positions and some of his ideas were enacted. More than that, his status as a martyr soon grew enormously and he became revered by the Mexican left and the state itself, which eventually began raising statues of him, renaming streets after him and even putting his face on banknotes. The legacy of his righteous revolution against a reactionary Mexican state echoed through time and following movements wished to emulate him. He was perhaps most beloved by the indigenous Mexican communities in Mexico’s most impoverished regions, which is where Chiapas comes into the picture.

While it’s common to picture Mexican people as a monolith, that’s not at all the case, especially so in Chiapas. In 2005, almost a million of the 3.5 million residents of Chiapas spoke an indigenous language other than Spanish with a third of these not speaking Spanish. These languages greatly vary and the specific indigenous groupings vary wildly as well, though they overwhelmingly have common roots in the Mayan civilizations. Due to a general lack of modernization and migration to the region (being one of the poorest states in Mexico), these indigenous communities have largely resisted Mexican cultural integration and have preserved a lot of their traditional culture, engendering a feeling of separation from and even hostility to the Mexican state.

This general feeling of neglect and the high levels of poverty, coupled with what was at the time an authoritarian Mexican government, led to significant instability and unrest in the population. Many regions at this time had their own active revolutionary groups and Chiapas had the National Liberation Forces (FLN) which was founded in 1969 and survived until its brutal disbandment in 1974 after the storming of their base and capture and subsequent torture of many leading members. While not a significant force in itself, former members later became influential in the Zapatistas and they’re a good indication of the volatility of the time.

On the 17th of November 1983, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) was formed clandestinely and began ingratiating itself into the population and existing peasant movements in Chiapas. Through alliances with other movements and non-violent political activism that kept the state off their back, they gradually grew a sizable membership that would soon dwarf many of their rivals. While not engaging in violence, they did however develop a military structure, secure arms and begin training for a conflict that seemed all but inevitable.

The Zapatista Revolution

On the 1st of January, 1994, NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement) came into effect. That very same day, the Zapatistas declared war on the Mexican government. You see, the purpose of NAFTA was to widen the scope of foreign investment between the USA, Canada and Mexico. In order to do that, barriers to trade had to be dissolved, which included altering Article 27 of the Mexican constitution which stated that indigenous communal landholdings could not be sold or otherwise privatized. This was the greatest direct legacy of Emiliano Zapata’s actions and by repealing it, indigenous communities and farmers feared being driven off their land by foreign investors.

On that very same day, Zapatistas seized control of seven towns across Chiapas and began seizing government buildings and occupying them. Police stations were burned, land records were destroyed and many political prisoners were freed while guns were seized for the rebels. In most cases, the rebels fled the city within hours and before a government response could even occur, although when the military intervened the following day, fighting occurred in several of these towns which led to around 300 deaths in total. Massive marches were held in support of the rebels in the Mexican capital and with international pressure mounting, Mexico declared a ceasefire on January 12th.

The Zapatistas swiftly began occupying smaller villages throughout Chiapas while negotiations continued, flexing their strength and popularity in the region while the government tried to reassure foreign investors that there was nothing to worry about. This state of affairs continued for about a year until the government launched an offensive in February of 1995. The official Zapatista response to the end of negotiations was a simple message of “See you in Hell.” The Zapatistas broke through the Mexican army blockade and fled into the Lacandon jungle where their leaders became impossible for the government to locate.

With the failure to immediately capture the Zapatista leaders and put an end to the uprising, coupled with the relative pacifism of the Zapatista forces that only enhanced the image of Mexico’s brutality in the eyes of the world, peace negotiations were reluctantly restored in April of the same year. Peace talks stumbled along uncertainly for some time until the start of the San Andrés Accords on the 16th of February, 1996. These talks continued for several months and the Zapatistas ensured that the government followed their basic demands.

The Zapatistas had five particular demands for the accords. Firstly, that the government respect indigenous people’s rights, culture and land ownership. Secondly, the government must work to ensure democracy and justice for indigenous groups. Thirdly, that all political prisoners be freed. Fourthly, that the military offensive in Chiapas be halted and pro-government paramilitaries disarmed. And finally, that a government delegation work with a Zapatista mediation body to resolve the conflict peacefully. All seems rather fair.

From here, the official hostility between the Mexican government and the Zapatistas reached its conclusion… Though that was hardly the true end of it. All the same, the Zapatistas were once again free to govern their territories in co-ordination with the indigenous peoples there and their influence gradually expanded. Negotiations continued into the 2000s, boosted significantly by the election of Vicente Fox in April of 2001, the first president not to belong to the previous authoritarian government in over 70 years. It was he who continued negotiations with the Zapatistas main representative. Subcomandante Marcos.

Subcomandante Marcos

While the Zapatistas lack a formal leader, they have a spokesman and ‘face’ in Subcomandante Marcos, the military leader and chief negotiator with the Mexican government. His title ‘Subcomandante’ emphasizes that he’s not the leader of the movement, but rather subordinate to the indigenous committees that make up the Zapatista political and governmental system. He is nonetheless a highly respected and influential figure, sometimes viewed as Mexico’s Che and with a mythos as grand.

It should be noted that Marcos is not actually his name. His real name is Rafael Sebastián Guillén Vicente, but nobody knew that for a long time. You might have noticed the balaclava he’s wearing, which is almost permanently on him and serves as a Zapatistas symbol. His anonymity sparked fear in the Mexican government who had nothing to go on when confronting this invisible foe in the jungles. When he was identified in January of 1995, just before the invasion, it only further weakened the Mexican government’s claims of him being a dangerous terrorist as those who knew him identified him as a staunch pacifist who had grown up in a Jesuit school.

Born in 1957 in Tampico as a ‘Mestizo’ (mixed Spanish and indigenous heritage), Subcomandante Marcos only moved to Chiapas in 1984 after a period of teaching at a university. He had involved himself for a time with the earlier mentioned FLN before becoming a founding member of the Zapatistas, quickly distinguishing himself with his military capability, intelligence, political education and charismatic personality. It was he who officially declared the war against the Mexican state and he who stood at the forefront of all negotiations thereafter.

Subcomandante Marcos’s greatest contribution to the movement was his personality, which he used to full advantage in getting the plight of Chiapas known to the world at large. Speaking English, on the first day of the revolution when the Zapatistas seized the city of San Cristóbal de las Casas, by pure coincidence due to the wounding of an ally, Marcos found himself transporting weaponry to the town square where he was met by many tourists and even foreign reporters. Reportedly, from 8am to 8pm, Marcos remained there interacting with locals and tourists, while giving four official interviews to journalists which made him the movement’s spokesperson.

By pure happenstance, he had become the figurehead and soon was granting constant interviews and negotiating with the Mexican state. Further, he was a prolific writer with dozens of books, hundreds of articles and quite likely thousands of interviews. He had a flair for writing and would often write elaborate prose and spread political messages through allegorical tales of fiction or even outright novels like his 2005 detective story “The Uncomfortable Dead.”

While Marcos established himself as a figurehead for the movement, he never truly wished for this. In May of 2014, he gave a public speech in front of thousands in which he stated that Marcos was a ‘hologram’ and an invention because the Mexican government and world at large would not see the people of Chiapas as a collective. It had been useful for a time but that time had passed. He announced the end of the persona and renamed himself to Subcomandante Galeano, in honour of a fallen comrade of his. From this time on, he took a back-seat and no longer served as the public face of the Zapatistas, though he continued to write and appear publically.

While the man himself no longer called himself Subcomandante Marcos, he had some choice words on the ‘character’ when asked whether he was gay. It is perhaps in this response that we can best understand what exactly it was to be Marcos.

“Yes, Marcos is gay. Marcos is gay in San Francisco, black in South Africa, an Asian in Europe, a Chicano in San Ysidro, an anarchist in Spain, a Palestinian in Israel, a Mayan Indian in the streets of San Cristobal, a Jew in Germany, a Gypsy in Poland, a Mohawk in Quebec, a pacifist in Bosnia, a single woman on the Metro at 10pm, a peasant without land, a gang member in the slums, an unemployed worker, an unhappy student and, of course, a Zapatista in the mountains.

Marcos is all the exploited, marginalised, oppressed minorities resisting and saying `Enough’. He is every minority who is now beginning to speak and every majority that must shut up and listen. He is every untolerated group searching for a way to speak. Everything that makes power and the good consciences of those in power uncomfortable — this is Marcos.”

Rafael Sebastián Guillén Vicente

Government in Zapatista Territory

Territories held by the Zapatistas are known as the Rebel Zapatista Autonomous Municipalities (MAREZ). These territories are not directly governed by the EZLN itself, rather they ensure the form of local democracy that functions there, which I’ll now try to explain.

There are three stages to the function and running of Zapatistas territory. First are the MAREZ, the bedrock of society. A community aligned with the Zapatistas forms a MAREZ which represents just their community and typically contains around 300 families in which every person over the age of 12 is entitled to a vote. There is aim towards consensus, but majority rule can be a fall-back if such consensus is impossible. By limiting the scope of the MAREZ, it does not infringe too much upon the cultural differences between indigenous communities, some of which may become marginalised.

The second stage is the ‘zone’, which is a collective of MAREZ’s that agree to join with one-another and co-operate by expanding on their democratic decision-making. This is useful for coordinating inter-communal trade and general decision-making without impeding on the local governance of one-another.

Thirdly is the ‘caracol’, which is the administrative center of each zone. The caracol has been described as being like a city hall, which is the place where decisions regarding the zone are addressed. The caracol is also typically where public meetings and internationally significant events take place, giving the Zapatistas a hub to interact with and present themselves to the rest of the world. ‘Caracol’ itself means ‘snail’, symbolically representing both the defensive nature of these communities and their willingness to take time in achieving their goals. The spiral pattern of a snail’s shell has also been thought of as symbolic of how power radiates outwards from the caracol through each zone.

Not everything is run through direct democracy, it should be noted. There are limited governing bodies known as ‘good government councils‘. These are the functioning body of the caracoles and contain representatives from each MAREZ. They are also overseen by the Indigenous Revolutionary Clandestine Committee’s General Command (CCRI-CG) of the EZLN, by mutual agreement, who ensure that the councils are not becoming corrupt.

The good government councils have several regulations in place. Firstly, that donations and support from civil society cannot be directed towards any particular individual or community, rather all funding goes to the council who decide collectively on what should be done with it and where. What’s more, each project in a location is charged a 10% ‘solidarity tax’ which is equally distributed among the communities not getting help from the project.

Additionally, only individuals and collectives that are registered with the councils are recognised as being Zapatistas, as well as that Zapatista companies that generate profit by marketing their products will have those profits (just profits, not the recouping of losses) taken by the council which will then be used to support other, smaller businesses that do not have the ability to market their products.

If it sounds like these councils place undue levels of power in the hands of a few individuals, I should explain how one gets there and how long they can stay. Every single member of the community has the right and indeed obligation to represent their community in the council. Once they have ended their mandate in the council, they cannot join the council again until every other person in that community has been in the role. Which, naturally, would make you wonder how long they’re in it for. And that varies from community to community, being set by the will of the caracol. In Oventik, the council rotates members every 8 days, while in La Realidad, it’s every two weeks.

As of now, and since a major expansion in 2019, there are 12 caracoles and 31 MAREZ’s. Not bad for a quasi-anarchist group.

Life in Zapatista Territory

So that’s all the governmental stuff taken care of, so let’s look at what it’s actually like to live there, shall we?

As the region of Chiapas is still among the poorest in Mexico, you’re not exactly going to see bustling cities under Zapatistas control. It’s primarily small villages and towns with majority indigenous populations that focus their economy on agriculture and handicrafts. Coffee especially is central to the economy under Zapatistas control and many agricultural collectives were developed where those who lived in the area controlled the growing of the coffee and the direct selling of it to distributors, particularly small businesses that agreed with the Zapatistas aims. These co-operatives are run democratically, without any ‘bosses’ and instead has a council that convenes once a year and elects representatives every three years.

All land is commonly owned with no private ownership to speak of. Workplaces and agricultural centers are similarly collectivized to the coffee plantations, though there is also an abundance of small craftsmen and traders which is in line with traditional culture in the region. They have aimed to end exploitation, though have not gone so far as to pursue Marxist socialism by eliminating commodity production or removing themselves from the global capitalist system.

The Zapatistas run their own schools based upon democratic education, in which students have a say in the curriculum and standardised grading is not used. This has limitations as far as the global market goes, but as higher education opportunities are already financially unviable for many in the region, this system is more oriented at the internal development of Zapatistas territories than preparing students for working in the rest of Mexico or the world at large. Other education from the state is also available of course.

Healthcare in Zapatistas territory is also a universal right, with the only payments needed being for certain medicines, purely to recoup costs of procuring them. While the quality of healthcare may be eclipsed by the most wealthy regions of Mexico, it has been noted to be drastically superior to that of the healthcare in the rest of Chiapas under government control.

The Zapatistas are also notably highly feminist, challenging the traditional male-dominated culture of Mexico and indeed, of the indigenous communities in many cases. On the day of the uprising, the Women’s Revolutionary Law was also put into effect, which included ten passages related to women’s rights. Rights in participation in revolutionary struggle, in salary, in choosing the number of children they can have, participation in community affairs, primary care, education, choosing their partners, to not be mistreated, to hold leadership positions and to be covered by all other revolutionary laws and regulations.

Each community has its own form of police service which functions more akin to a neighborhood watch. There is an emphasis on restorative justice as opposed to punitive action, with reportedly only two people in ‘prison’ in the entirety of their territory. With those two people supposedly being outsiders who planted marijuana in the area to attempt to convince the military to intervene with the war on drugs as a pretext.

Also notable is the phenomenon of ‘Zapturismo’, tourism into Zapatista territories. Very relevant to us, you might think! And they certainly do support this, up to a certain point at least. They’re perfectly happy to accept outsiders into their territory for the purposes of tourism, but utterly reject government attempts to facilitate expanded tourism through commercial train lines or hotel chains, seeing such suggestions as a ‘declaration of war’ due to its lack of purpose or aid to the local communities.

Conclusion

So this has been one very long introduction to the world of the Zapatistas. An extremely unique movement that really deserves more recognition. They’ve gotten it here and there, with Rage Against The Machine possibly being more closely affiliated with their flag than they are, but with their gradual expansion and the clear demonstration of their success, it’s entirely possible that the Zapatista snail will come out on top.

If you’d like to know more about their ideas and how they function, the works of Subcomandante Marcos are definitely a great place to start. As is the 2005 ‘Sixth Declaration of the Selva Lacandona‘, which functioned as a manifesto for the movement going forward. Meanwhile if you’d like to see more interesting things in Latin America, check out this article on a very interesting news program from Venezuela under Chavez!

If you’ve gotten interested in the Zapatistas from this article, then good! Go order some of their communally produced coffee, maybe. And if you’d like to see them yourself, they do accept visitors! As for whether we’ll run tours there some day… Well, this is no confirmation, but never say never.