By Dean Karalekas

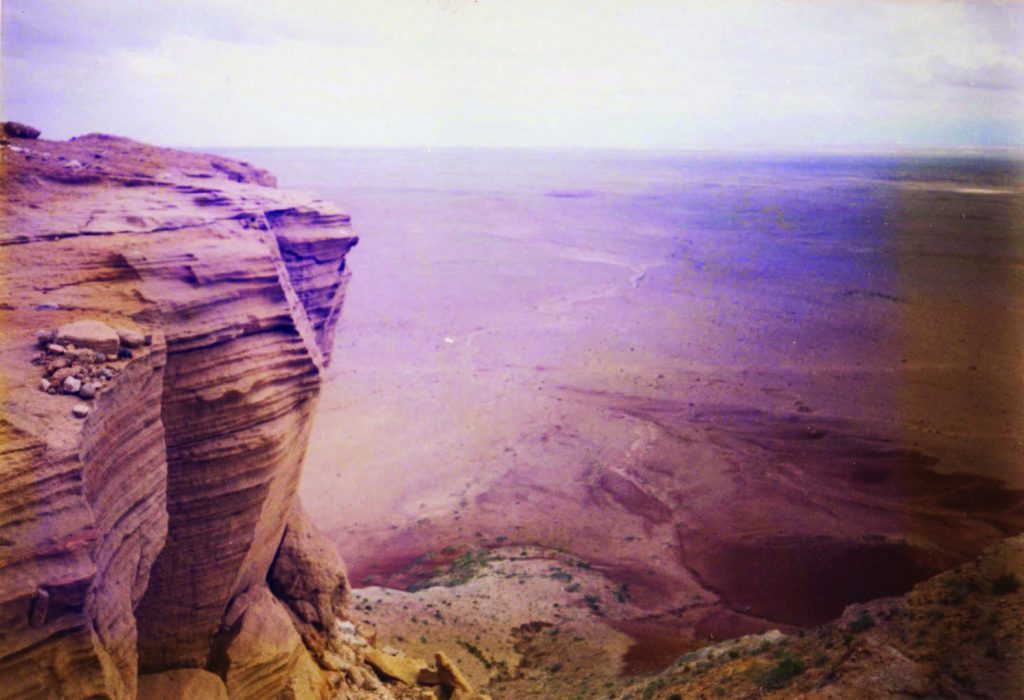

Outer Mongolia in the 1990s was not a tourist destination. Entry visas were difficult to secure, and there was precious little tourism infrastructure outside of the capital, Ulaanbaatar. The Berlin Wall may have fallen a few years earlier, but a Communist party was still in power. In an era when thousands of backpackers from Europe and North America were converging on Bangkok’s Khao San Road to enjoy banana pancakes and pirated VCDs while planning their next full-moon rave, few evinced an interest in venturing so far north to a windswept desert country. Especially one without a beach.

But this is where I found myself after a year teaching English at a hagwon in South Korea—every Canadian, it seemed, did a stint teaching English in South Korea or Japan in those days, the job market being what it was back home. At the end of my contract, my wonjangnim owed me a one-way ticket back to Vancouver. Save some money, I told him: get me a ticket to Ulaanbaatar instead. He was happy to comply.

My interest in Mongolia was piqued by a travel piece on Korean TV, with images of a wide, sparsely populated square in a bleak city. It seemed so remote; so alien. The edge of the world. I mentioned it that weekend drinking in this or that Itaewon bar, and got an answer from Merrill, a friend of a friend. “Oh, that sounds like Sukhbaatar Square,” he said. “Mongolia. I used to live there.”

Merrill explained that he was once in the Peace Corps, and was stationed in a small village in a remote part of the country. He gave me the name and phone number of a contact of his there, a professor who helped the Peace Corps in their work. Mr. Khurelbat could arrange an invitation—invitations were required, and almost exclusively issued by the government-run tourist agency Juulchin (equivalent to the Soviet Intourist) for a hefty fee. I called Khurelbat, and he agreed to fax me an invitation, as well as arranging an apartment in Ulaanbaatar I could rent for the month.

The journey to Mongolia

Invitation and plane ticket in hand, I took the day off work to visit the Mongolian embassy in Seoul to secure my visitor’s visa. The address I was given brought me to a large residential building on the south bank of the Han River. This can’t be right, I thought. People live here. I went to the apartment number and knocked, and a kind, elderly woman answered the door, and ushered me into the living room. As she made tea in the kitchen, her husband appeared from the bedroom and introduced himself. It turns out he was indeed the Mongolian ambassador. He inspected my invitation and asked me for my passport. He produced a stamp and ink from a cigar box under the coffee table, and duly stamped a visitor’s visa into one of my many empty pages. Clearly, there was virtually no demand in South Korea to visit Mongolia, and I began to worry about what they knew that I was yet too stupid and too green to have figured out.

I spent the flight staring nervously down at the never-ending expanse of the harsh Gobi desert below—as a Canadian, this was unknown territory for me—after which Khurelbat met me at the airport and dropped me off at the apartment, and quickly left me alone to settle in. He was using one of the rooms for storage … boxes of various commodities, some of them dry goods. The only entertainment was a small beige Bakelite radio attached to the wall in the corridor. It had one switch—on and off—and hence one channel, that played what I could only assume was government propaganda, interspersed with the occasional revolutionary opera.

Rummaging around in the storage room, I found an old Soviet-made shortwave radio. Excited at the prospect of listening to more than just “Ode to the People’s Tractor,” I ventured out to try to find the D cell batteries it required. An excellent excuse to get acquainted with the city.

The Spartan streets and slow pace was in distinct contrast to the hustle and bustle of the Korea I had just left. Grocery store shelves were largely bare, and shopping consisted primarily of the stolid State Department Store and a black market that popped up occasionally in the north of the city. I found some batteries—as well as an English copy of “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?” by Philip K. Dick—at a makeshift flea market just outside the Post Office.

I hurried home to try out my new home entertainment system. Batteries in place, I twisted the knob through every frequency available on the enormous front panel. Nothing. It only received signals from a single frequency, and it was the same one emanating from the wall unit. More operas praising the motherland, industrial workers, and the patriotic heroes of the Party.

Dejected, I hunted through the storage room and found a screwdriver that I used to remove the back panel, to take a look at the radio’s innards. I’m no electronics engineer, but what else was I going to do with my time? Poking through the plate of spaghetti that was wires and circuitry, I found a single wire hanging loosely out of place. Judging by its length, I guesstimated which pad on the green circuit board it must have once been attached to, and started hunting for a soldering iron. No such luck.

One last chance: I turned on the range on the stovetop and slipped the screwdriver in the element to heat up. After a few tries, I managed to get the screwdriver to hold enough heat to solder the wire back into place, and after reassembling the unit, I turned it on. The first noise to come out of the box were the triumphant strains of Freddie Mercury belting out “We Are The Champions.”

Success! The radio picked up every station: Voice of America; the BBC; Radio Canada International. I even picked up the North Korean propaganda channel, Voice of Korea—jammed in the South—with music and news in English from the Hermit Kingdom. No news of the famine that was occurring at that time, but Kim Jong-il was busy inspecting factories and conferring medals upon hero farmers.

The following day, I dropped in to check in with Mr. Khurelbat and meet the Peace Corps kids. I was impressed with their intelligence and maturity. They were surprised to meet a tourist, and whenever I’d tell them about meeting Merrill in Seoul, their face would twist into an expression of deep concern, and they’d lower their voice to ask how he was doing. He’s fine, I assured them. But this happened so often I just had to ask about it. One young man explained to me that Merrill had had a bit of a nervous breakdown while on deployment, and had taken an axe to his ger. Called a yurt in Siberia, a ger (the traditional Mongolian house) is a felt and lattice-wall tent that provides a warm home for nomads of the remote desert, or up in the windswept steppes. It can be broken down and rebuilt in less than an hour, after the seasonal move to fresh grazing land. Merrill had obviously had enough of the isolation and the strain of culture shock, and after his rampage, had to be airlifted out. That was the last they’d heard of him. They were happy for the news that he was doing well in South Korea.

A time before foreigners

In those days, there was little for the foreigner to do to pass the time in Ulaanbaatar, other than drinking to excess at the Bayangol Hotel bar, frequented by miners, hookers, freedom fighters, and smugglers working the China-to-Eastern Europe route. This is where I spent most of my time in those days, and I found ready acceptance into this small but friendly community. Being alone on the edge of the world is an insular existence, and any new faces like mine were enthusiastically welcomed (read: interrogated) by the older hands—new grist for the rumour mill.

It was here that I met Mike and Mike, a pair of German adventurers cursed with the same name. After conducting various experiments on who could imbibe more alcohol, Germans or Canadians (Germans, it turned out), we were about to go our separate ways at closing time when they announced that they were heading south tomorrow morning, to the Gobi Desert, and would I like to come along, to share the cost. I readily accepted their kind offer, and rushed back to the apartment to pack. I only hoped that, once the effects of the alcohol wore off, they would remember inviting me.

Taking the train in Mongolia

The following morning we met up as arranged and boarded the train to Sainshand, the capital of Dornogovi Province. There we met our guide Oktai and driver Altan, and threw our baggage into what was to be our home and chariot for the next week: a UAZ 469 Russian jeep.

At the time, I was unfamiliar with this model of off-road military light utility vehicle, but by the end of the trip I would be a convert to the excellence of Soviet automotive engineering. It was like a Kalashnikov rifle: it was reliable, it never jammed no matter the conditions, and it had few moving parts you couldn’t fix with the most basic of tool kits. Moreover, it could handle any terrain.

For example, at one point on our journey, long after we had left the road behind and were rattling over raw desert, as the Mikes and I played car bingo with the species of wild animals we could spot—wild horses, camels: at one point we thought we saw a wolf; a sign of good luck here in the Gobi—we passed close to a herd of black-tailed gazelle. Without pausing a beat, Altan kicked it into gear and started chasing down the herd as Oktai leaned back and beckoned for his rifle. At top speed, the octogenarian kicked open his door and balanced his firearm in the crook. As the wind suddenly invaded the cabin, I exchanged glances of amazement and confusion with my fellow passengers. With a single shot, Oktai expertly wounded one of the fleeing antelopes, slowing it down enough for us to close in for the kill with a quartering-away shot.

We all got out and marveled as Altan expertly field-stripped the animal, discarding the offal and wrapping the liver, and strapped the carcass to our roof. That night, we made a gift of our trophy to a nomadic herder and his family, in exchange for their hospitality in allowing us to sleep in their ger. The patron offered me a pinch of snuff from an enormous bottle, and I learned that snuff bottles are also a status symbol here: the larger it is, the richer the man. The wealth of a Mongolian herder is reckoned not by the numbers in his bank account, but by the numbers in his herd.

Eating a gazelles liver in Mongolia

That night we cooked the gazelle’s liver on a fire fueled by cattle dung, there being no trees in the desert. We sat around the hearth eating, smoking cigarettes, exchanging stories with our hosts, and drinking vodka in the traditional Mongolian manner: served hot, in a silver-lined wooden bowl, with yak butter and salt. As we were guests who had traveled a great distance to be there, most meals became a special event demanding round after round of Mongolian vodka.

This is how we spent each of our nights: driving through the desert and seeking a remote homestead upon whose hospitality we could rely for shelter, in exchange for whatever gifts we had brought along. Mike delighted in introducing the Mongolian children to that marvel of Western technology, the drink’n box. How their eyes lit up. He also had a Walkman, and would let them listen to whatever German thrash metal band he had on cassette tape. The kids were less enthusiastic about that bit of cultural exchange, wanting more of the drink’n box.

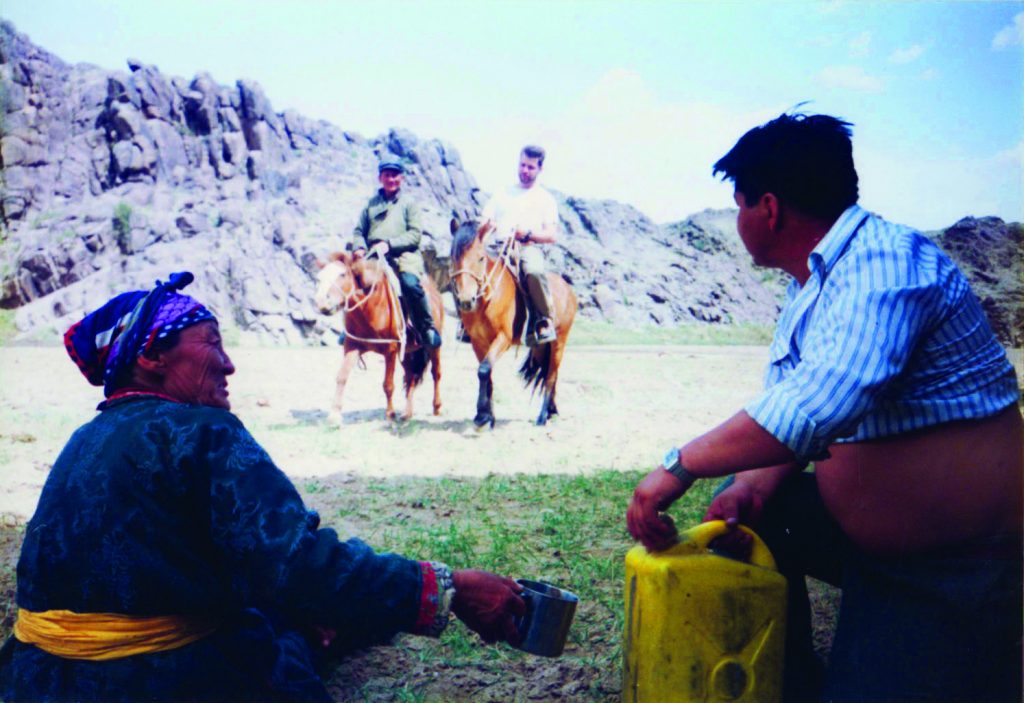

We saw much more, just by serendipity, driving around the Gobi than could ever have been planned by a tour guide in Ulaanbaatar the Mongolian capital. We walked in Zuunbayan with fossils crunching underfoot, where I imagined Roy Chapman Andrews must have found the dinosaur eggs that saved his bacon. We dined with a local magistrate, who tracked us down to make sure he wasn’t hallucinating, after seeing foreigners—foreigners!—a long distance off, watering camels at a lonely desert well. We happened upon a group of tomb raiders excavating a half-buried Buddhist monastery, which had been destroyed in the 1930s in the Stalinist-inspired purges led by Choibalsan. They were harvesting bricks for use in another building project, but along the way unearthed several Buddhist sculptures and other votive objects. We bought what we could carry.

Leaving Mongolia

The Chinese border with Mongolia was the end of the line for us, and here we were welcomed by a lonely military outpost guarding the frontier. After spending a night drinking more vodka and trading more tall tales with the soldiers, it was time to head back to Ulaanbaatar—a sad prospect. Even sadder was saying goodbye to Mongolia to continue my travels south through China, The Philippines, Borneo, and parts West.

I never saw the Mikes again, or Oktai and Altan for that matter. These were the days before the Internet, and you didn’t bring your social circles with you on your travels. If you wanted to communicate, you had to fax, or at least call, provided you had access to a landline. Likewise, you couldn’t Google an answer to every question: sometimes the only place to get information was from a guy in a bar. And if you happened to bite the biscuit while so far off the beaten path, with no-one aware of your itinerary because you were making it up as you went along, then your fate would forever remain a mystery to your loved ones back home. We’ve gained much with the ubiquity of modern technology, but I think we’ve lost a certain degree of intrepidity as well. I have often thought about returning to Outer Mongolia, but the country has changed so much, I think I would rather hang on to my memories as they are. I guess home is not the only place you can’t go again.

Like what you read? You can buy Dean’s book here. Want to read more great content by Dean and others? Click here to subscribe.